Reliance on a purported technical effect for inventive step – Quo vadis “plausibility” after G 2/21?

In the context of the effect-driven assessment of inventive step under the European Patent Convention (EPC) it is usually crucial for the outcome whether an Applicant/a Patentee can rely on a specific technical effect corresponding to an improvement over the prior art. In the absence of such improvement, the claimed subject-matter is often found to be obvious. From the perspective of the Applicant/Patentee, flexibility is required to adapt an initially disclosed technical effect in case new evidence such as new prior art or new experiments comes up during examination or opposition proceedings. In a first-to-file system like the EPC, however, the Applicant/Patentee should also not be able to later invoke any effect at will to exclude purely speculative filings and corresponding unwarranted advantages for such Applicants/Patentees. In G 2/21, the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) is concerned with providing guidelines on how a proper balance can be achieved. The provisions of G 2/21 have meanwhile been applied in several decisions.

In the context of the effect-driven assessment of inventive step under the European Patent Convention (EPC) it is usually crucial for the outcome whether an Applicant/Patentee can rely on a specific technical effect corresponding to an improvement over the prior art. In the absence of such improvement, the claimed subject-matter is often found to be obvious. From the perspective of the Applicant/Patentee, flexibility is required to adapt an initially disclosed technical effect in case new evidence such as new prior art or new experiments comes up during examination or opposition proceedings. In a first-to-file system like the EPC, however, the Applicant/Patentee should also not be able to later invoke any effect at will to exclude purely speculative filings and corresponding unwarranted advantages for such Applicants/Patentees. In G 2/21, the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) is concerned with providing guidelines on how a proper balance can be achieved. The provisions of G 2/21 have meanwhile been applied in several decisions.

Background

In order to assess inventive step (Article 56 EPC) in an objective and predictable manner, Technical Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office (EPO) developed the so-called “problem-solution approach”. The Boards identified three main stages: (i) determining the “closest prior art”, (ii) establishing the “objective technical problem” to be solved, and (iii) considering whether or not the claimed invention, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person. The objective technical problem is formulated based on the technical effect resulting from the distinguishing feature(s) of a claim and the disclosure in the closest prior art. Depending on the technical effect, the corresponding problem may be the provision of an improvement or simply an alternative over the closest prior art. Alternative solutions are frequently rejected for being obvious. For this reason, Applicants/Patentees primarily attempt at relying on an improvement, which often can be argued to be unexpected and therefore nonobvious. The purported effect is therefore very often crucial in the evaluation of patentability.

Such an effect needs to be established i) per se and ii) over the whole breadth of the claim in order to be accepted, and a challenge very often concerns one or both aspects. During the lifetime of a patent application or patent, an originally disclosed effect may therefore be successfully challenged through evidence not yet considered by the EPO, such as new prior art or new experiments. If the Applicant/Patentee should not be limited to a less ambitious effect or even only an alternative in such a situation, the Applicant/Patentee should be able to adapt the originally disclosed technical effect. Consideration of “post-published” evidence, i.e. evidence not forming part of the original application, might become necessary to establish the adapted effect both per se and over the whole breadth of the claims. As an Applicant/Patentee may not at the time of filing the application be aware of prior art or other evidence that might come to light only later during prosecution/post-grant proceedings, some flexibility is needed to allow the Applicant/Patentee to defend its case in such situations. However, as the EPC is based on the first-to-file principle, an Applicant/Patentee is generally not allowed to invoke any technical effect at will after the application has been filed, in particular in situations where the application as filed does not disclose any kind of solution and subsequently produced evidence is the first material going beyond mere speculation. The invention in essence must be disclosed in the application as originally filed.

There is no straightforward answer to the question of under which circumstances an Applicant/Patentee may or may not rely on post-published evidence to establish a technical effect which will be taken into account for the assessment of inventive step and which often will be essential for establishing patentability. On the one hand, care must be taken that no unfair advantage is given to the Applicant/Patentee, and on the other hand, the Applicant’s/Patentee’s ability to defend its case should not be unduly restricted when circumstances change unforeseeably. The catchword “plausibility” has been used in the past to encapsulate the problem of when to allow or disallow post-published evidence.

On March 23, 2023, the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) issued its much-awaited decision on this topic, G 2/21.

Below, the facts underlying G 2/21 will first be summarized. The EBA’s guidelines in G 2/21 will then be reviewed. Following that, the reasoning of the Technical Board 3.3.02 for admitting post-published evidence in the underlying case T 0116/18 and following the guidelines in G 2/21 will be outlined. Finally, an overview of currently available decisions applying G 2/21 in the context of Art. 56 EPC will be provided.

The facts underlying G 2/21 – a short recap

Claim 1 in the underlying case T 0116/18 was directed to an insecticide composition comprising thiamethoxam and a compound represented by formula Ia.Reason 1.1 of T 0116/18 (decision of July 28, 2023, published November 2023). The claimed subject-matter differed from the closest prior art in that both thiamethoxam and the compound according to formula Ia had to be selected from a respective broader disclosure in the closest prior art.Reason 6 of T 0116/18. The finally adapted relevant purported technical effect was an improvement due to a synergistic activity between thiamethoxam and a compound according to claim 1 against the insect Chilo suppressalis.Reason 13 of T 0116/18.

According to the application as filed, a synergistic effect between the more general formulae I (comprising subset Ia as claimed) and II (comprising thiamethoxam as claimed) against insects in general can be achieved.Reason 17.1 of T 0116/18. The application contained five test examples evaluating the presence/absence of synergy between two insecticides.Reason 3 of T 0116/18. Test example 3 related to Chilo suppressalis, but the tested insecticide compositions were not according to granted claim 1.Reason 17.1 of T 0116/18.

In the course of the opposition proceedings, the Patentee filed post-published evidence which in the referring Board’s view was sufficient proof of a synergistic effect against Chilo suppressalis across the entire breadth of claim 1 as granted.Reasons 4 and 6 of T 0116/18. According to the referring Board, the problem to be solved consisted therefore in the provision of an improved insecticide composition and the solution to this problem would be considered unobvious if the post-published evidence showing synergy for the claimed combination were to be accepted, while the claimed subject-matter would be only an obvious alternative insecticide composition if not.Reasons 6 and 22.1 of T 0116/18. Patentability hinged solely on the post-published evidence.

The referring Board discussed three purportedly diverging lines of earlier case law from the Boards of Appeal regarding the circumstances under which post-published evidence can be taken into account on substantive grounds:

-

(i) Type I case law: post-published evidence can be taken into account only if, given the application as filed and the common general knowledge at the filing date, the skilled person would have had reason to assume the purported technical effect to be achieved, or, in other words, if the effect is already “credible” from the application as filed (“ab initio plausibility“). A representative example is T 1329/04. The burden of proof for ab initio plausibility usually rests with the Applicant/Patentee;Reasons 13.4 and 15 of T 0116/18 referral (interlocutory decision of October 11, 2021).

-

(ii) Type II case law: post-published evidence can only be disregarded if the skilled person would have had legitimate reasons to doubt that the purported technical effect would have been achieved on the filing date of the patent in suit (“ab initio implausibility“). A representative example is T 0919/15 which, like the referral case, concerned a synergistic effect. The burden of proof for ab initio implausibility usually rests with the opponent;Reasons 13.5. and 15 of T 0116/18 referral. and

-

(iii) Type III case law: rejecting the concept of plausibility altogether (“no plausibility“). An example is T 0031/18, in which the Board held that a technical effect must either be explicitly mentioned in the application as filed or at least be derivable therefrom, but without requiring a specific level of plausibility.Reason 13.6 of T 0116/18 referral and reason 65 of G 2/21.

The guidelines of the EBA

The EBA explained that, according to established jurisprudence of the Boards of Appeal, inventive step is to be assessed at the effective date of the patent on the basis of the information in the patent together with the common general knowledge then available to the skilled person.Reason 23 of G 2/21. An effect cannot be validly used in the formulation of the technical problem if the effect required additional information not at the disposal of the skilled person even after taking into account the content of the application in question.Reason 25 of G 2/21.

Having analyzed a selection of jurisprudence in the context of the three different approaches use by the referring Board (type I, II, and III case law, supra),3 the EBA found that the core issue common to all decisions rests with the question of what the skilled person, with the common general knowledge in mind, understands at the filing date from the application as originally filed as the technical teaching of the claimed invention.4 According to the EBA:5

Having analyzed a selection of jurisprudence in the context of the three different approaches use by the referring Board (type I, II, and III case law, supra),Reasons 65 to 69 of G 2/21. the EBA found that the core issue common to all decisions rests with the question of what the skilled person, with the common general knowledge in mind, understands at the filing date from the application as originally filed as the technical teaching of the claimed invention.Reason 71 of G 2/21. According to the EBA:Reason 72 of G 2/21.

“Applying this understanding to the aforementioned decisions, not in reviewing them but in an attempt to test the Enlarged Board’s understanding, the Enlarged Board is satisfied that the outcome in each particular case would not have been different from the actual finding of the respective board of appeal. Irrespective of the use of the terminological notion of plausibility, the cited decisions appear to show that the particular board of appeal focused on the question whether or not the technical effect relied upon by the patent applicant or proprietor was derivable for the person skilled in the art from the technical teaching of the application documents.” (emphasis added)

On this basis and without rejecting the reasoning of any cited decision in its substance, the EBA stated in order no. 2:

“A patent applicant or proprietor may rely upon a technical effect for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would derive said effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.”

In its concluding remarks, the EBA emphasized:Reason 95 of G 2/21.

“The Enlarged Board is aware of the abstractness of some of the aforementioned criteria. However, apart from the fact that the Enlarged Board, in its function assigned to it under Article 112(1) EPC, is not called to decide on a specific case, it is the pertinent circumstances of each case which provide the basis on which a board of appeal or other deciding body is required to judge, and the actual outcome may well to some extent be influenced by the technical field of the claimed invention.” (emphasis added)

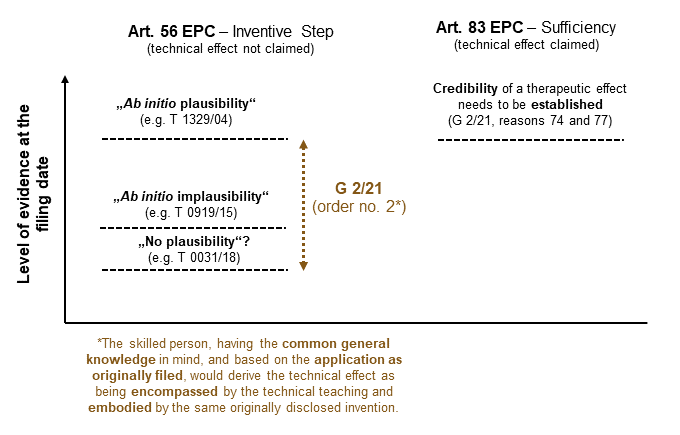

Although the referring questions did not require an answer on the issue of sufficiency of disclosure under Art. 83 EPC, the EBA accepted the appropriateness of a comparative analysis and comparative considerations in this regard.Reason 73 of G 2/21. The corresponding statements are also interesting for a better understanding of its guidance under Art. 56 EPC. The EBA stated that the notion of “plausibility” has been used in particular in the context of second medical use claims. According to the EBA, a technical effect, which in the case of second medical use claims is usually a therapeutic effect, is a feature of the claim, so that the issue of whether it has been shown that this effect is achieved is a question of sufficiency of disclosure. Hence, according to the EBA, because the subject-matter of second medical use claims is commonly limited to a known therapeutic agent for use in a new therapeutic application, it is necessary that the patent at the date of its filing renders it credible that the known therapeutic agent, i.e. the product, is suitable for the claimed therapeutic application.Reason 74 of G 2/21. It added that the scope of reliance on post-published evidence is much narrower under sufficiency of disclosure (Art. 83 EPC) compared to the situation under inventive step (Art. 56 EPC).Reason 77 of G 2/21. The EBA also stated:Reason 77 of G 2/21.

“In order to meet the requirement that the disclosure of the invention be sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by the person skilled in the art, the proof of a claimed therapeutic effect has to be provided in the application as filed, in particular if, in the absence of experimental data in the application as filed, it would not be credible to the skilled person that the therapeutic effect is achieved. A lack in this respect cannot be remedied by post-published data.”

The more limited scope and very different wording provided for second medical use claims under Article 83 EPC emphasizes the broader scope under Art. 56 EPC.

The main conclusions that can be drawn from G 2/21

-

There is no indication that the EBA wished to create an altogether new standard for evaluating whether an Applicant/Patentee can rely on post-published evidence to back up a technical effect under inventive step considerations. Rather, it formulated a test which it considered common across the existing jurisprudence. This test therefore can be seen to encompass the previous standards, and at least the decisions analyzed in G 2/21 appear to retain their validity as references.

-

The EBA focused on the application as filed and the understanding of the skilled person as at the filing date, emphasising that an invention cannot be solely based on knowledge made available only after the filing date. It did not give carte blanche to reliance on any technical effect and to using post-published evidence in all instances.

-

The criteria in order no. 2 remain rather abstract and there is consequently no clearly defined common standard. The decision must rest on the specific facts of the particular case and may also depend on the technical field of the claimed invention. Consequently, G 2/21 allows great flexibility for the Boards to reach decisions on a case-by-case basis. While existing case law can continue to apply, new case law can also be developed in different technical fields.

-

By way of comparing the much narrower guidelines of the EBA as regards sufficiency of disclosure (Article 83 EPC) for medical use claims and the requirements under order no. 2 for inventive step (Article 56 EPC) it can be concluded that a credible disclosure in the application as filed for a purported effect is not always a mandatory requirement under inventive step but will depend on the facts of each case.

The above main conclusions can be schematically summarized as follows:

The application of the EBA guidelines in T 0116/18

The referring Board relied on order no. 2 of G 2/21 and applied the two-fold test, namely whether the skilled person having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would consider the effect as being

-

(i) encompassed by the technical teaching, and

-

(ii) embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.Reason 11.3 of T 0116/18.

The Board first provided a general interpretation of order no. 2 and then applied its interpretation to the facts of the case.

In its general analysis the Board firstly noted that G 2/21 seeks to prevent speculative inventions and that there is no “carte blanche” for patent applicants or patentees:Reason 11.1 of T 0116/18.

“The Enlarged Board did not hold that a patent applicant or proprietor can always rely on a purported technical effect. On the contrary, the Enlarged Board, by way of order no. 2, established requirement(s) that must be met. The Enlarged Board thus did not give patent applicants and proprietors “carte blanche” to be able to rely on a purported technical effect at any stage of the proceedings. Therefore, it can be concluded from order no. 2 that patent applicants and proprietors should not be able to invoke any technical effect at will. Instead, the focus on the application as filed and the filing date (G 2/21, point 93 of the Reasons) is intended to prevent the filing of applications directed purely to speculative (armchair) inventions made only after the filing date.” (emphasis added)

The Board considered whether order no. 2 provides a new standard or is a summary of the old standards in the existing case law. The Board found that it would not matter since it is now the requirements of order no. 2 that have to be followed rather than simply using any rationale developed in the previous so-called plausibility case law.Reason 11.3.2 of T 0116/18.

The Board reasoned that both requirements of order no. 2 are separate requirements which must be met cumulatively.Reason 11.4 of T 0116/18. It concluded that

-

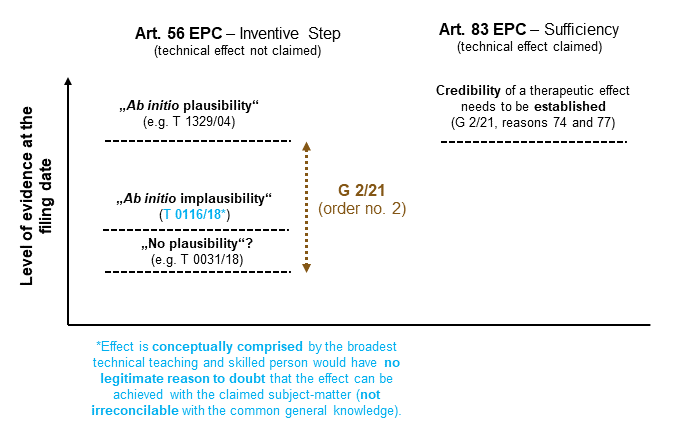

for requirement (i) to be met, the purported technical effect together with the claimed subject-matter need only be conceptually comprised by the broadest technical teaching of the application as filed, which in turn means that said effect need not be literally disclosed by way of a positive verbal statementReason 11.10 of T 0116/18., and

-

for requirement (ii) to be met, the skilled person, having the common general knowledge on the filing date in mind, and based on the application as filed, must not have legitimate reason to doubt that the purported technical effect can be achieved with the claimed subject matter. Experimental proof of the purported technical effect or a positive verbal statement is not necessarily required in the application as filed.Reasons 11.11 to 11.14 of T 0116/18.

It is noteworthy that when defining the conditions under ii) the Board used the same wording as it used for summarizing the “ab initio implausibility” standard in its referral decision, i.e. “would have legitimate reason to doubt that the purported technical effect can be achieved with the claimed subject matter“ (supra).

The Board then applied the general interpretation of order no. 2 to the facts of the case:

-

The Board found that the broadest technical teaching of the application as filed can be considered to be that a combination of a compound of general formula I with a compound represented by general formula II can result in a synergistic effect against insects. Regarding (i), the Board thus reasoned that the purported technical effect (i.e. the synergistic activity against Chilo suppressalis) is encompassed by the broadest technical teaching of the application as filed, because the compounds of formula Ia of claim 1 as granted are a subset of those of formula I, thiamethoxam as referred to in claim 1 as granted falls within the definition of formula II and Chilo suppressalis is a specific insect species and therefore falls under the corresponding broader term “insects”.Reasons 15 and 16 of T 0116/18.

-

Regarding (ii), the Board found that the application contains examples demonstrating a synergistic effect against Chilo suppressalis, although not for an insecticide combination in accordance with claim 1 as granted, but rather for a combination of clothianidin or dinotefuran (and not thiamethoxam as claimed) with a compound of formula Ia.Reason 17.2 of T 0116/18. The Board considered clothianidin and thiamethoxam to be structurally very similar and therefore concluded that the skilled person would have no legitimate reason to doubt that the synergistic effect against Chilo suppressalis would be maintained when replacing clothianidin with thiamethoxam (as in the claimed insecticide combination).Reason 17.4.1 of T 0116/18. In particular no concrete evidence was provided, derived from the common general knowledge, as to why the skilled person would have legitimate reason to doubt that the specific purported technical effect can be achieved.Reason 17.4.2 of T 0116/18. In order to specify such legitimate reasons to doubt, the Board indicated that it would need to see evidence showing that the purported effect is irreconcilable with the common general knowledge. In this context, it emphasized that the unpredictable and surprising nature of a synergistic effect in general was not sufficient to generate such doubts.Reasons 17.4.2. and 17.4.3 of T 0116/18.

The main conclusions that can be drawn from T 0116/18

-

The Board interpreted the guidelines given by the EBA in order no. 2 as a new test.

-

Post-published evidence cannot always be taken into account; rather the two conditions provided in order no. 2 need to be cumulatively fulfilled.

-

Post-published evidence cannot be disregarded solely because there is no verbal statement or no experimental proof in the application as filed.

-

This Board interpreted the purported new test condition ii) in order no. 2 still very much in line with the previous “ab initio implausibility” standard in its referral decision.

-

The Board nevertheless placed much emphasis on the experimental evidence in the application as filed and its supportive nature for the purported effect.

-

With the existing experimental evidence in the background, the Patentee in this case had the benefit of the doubt regarding remaining uncertainties while the burden of proof rested mainly on the Opponent.

In our opinion, the Board in T 0116/18 applied a standard falling within the range of order no. 2 of G 2/21, this standard (as outlined above) being very much in line with what this Board considered the “ab initio implausibility” standard in its referral:

Other decisions applying order no. 2 of G 2/21

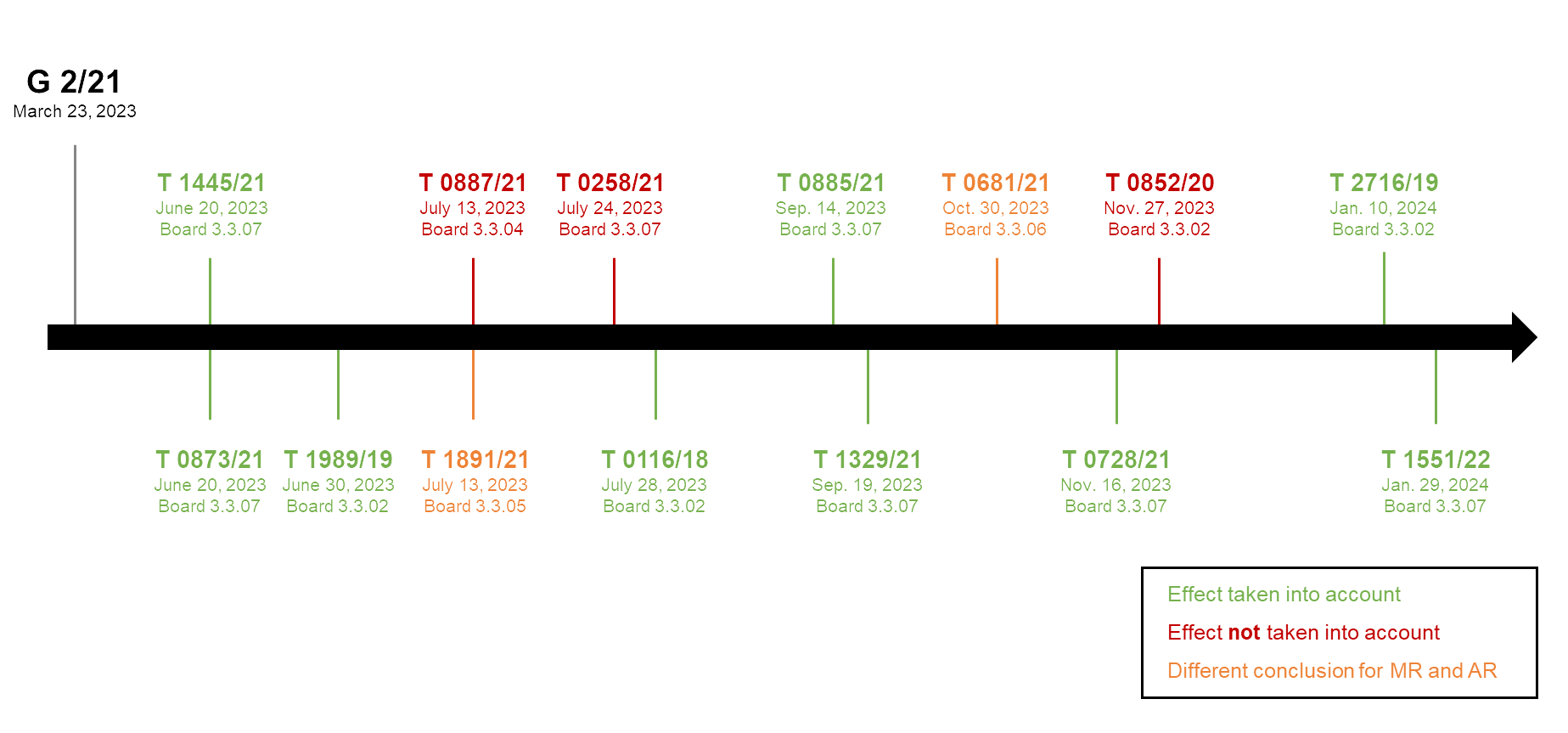

As of February 2024, we are aware of 14 decisions concerned with reliance on a purported technical effect in the context of inventive step which applied the test stipulated in G 2/21. Only decision T 1989/19 (also from Board 3.3.02) seems to have used a very similar approach as in T 0116/18. However, the other decisions did not apply the very same interpretation as provided in T0116/18 (supra). In summary, only about one third of the decisions rejected a purported technical effect and corresponding post-filed evidence while the majority of the decisions accepted it. Two decisions (T 1891/21 and T 0681/21) differentiated between main requests (MR) and auxiliary requests (AR). The decisions are summarized in the following timeline:

Summary

It would appear from current developments that there is a trend towards a lower standard for reliance on a purported technical effect (and post-published evidence) and higher burden on the Opponent to disqualify such effect and evidence. However, this may merely be due to the specific circumstances of the cases considered so far. As emphasized by the EBA, the deciding body is required to base its judgment on the particular circumstances of each specific case.

In any event, it seems to be not a foregone conclusion that the existing case law regarding the higher standard, i.e. more like the former “ab initio plausibility” standard, no longer applies. The EBA appears to have left this open.

Finally, T 0116/18 has also not yet been conclusively settled, since the Opponent filed a petition for review under Art. 112a(1) EPC on January 17, 2024 (see case number R 04/24). According to the Opponent, the requirements established by the Board under which criterion (ii) of order no. 2 of G 2/21 can be considered fulfilled (supra) constitute a new test that was not discussed at the hearing and therefore violated the Opponent’s fundamental right to be heard.